TICKET AVAILABILITY UPDATE

4 pm, Monday, 29 January:

1st Screening, TUESDAY: SOLD OUT

2nd Screening, WEDNESDAY: a few tix still available at outlets, the Internet and by phone.

W H A T :

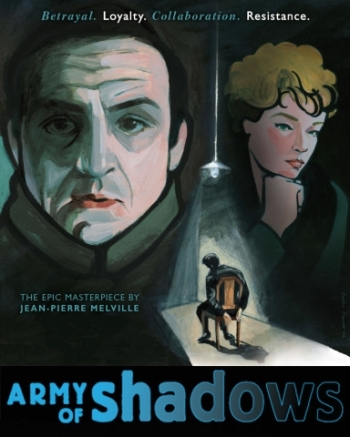

(L'Armee des Ombres) the epic masterpiece by director Jean-Pierre Melville.

W H E N :

W H E R E :

click for Directions & Map

T I C K E T S :

$6 tickets are available in advance - online, by phone, at the Art Museum Guest Services Desk; and at the door on the nights of the screenings. $6 tickets are NOT available at CWC ticket outlets.

ADVANCE TICKETS:

...and at these locations

($8 tix only, cash only),

click each location below for a map:

Sitwell's Coffee House

513 281 7487

Lookout Joe Coffee Roasters

513 871 8626

Shake It Music & Video

513 591 0123

Tickets will also be available at the door, if not sold out in advance.

Tuesday, January 30:

Dr. François Le Roy

Professor of Modern European and Military History at Northern Kentucky University, Dr. Le Roy teaches courses in modern French history and miltary history. A native of Brittany, France, he has relatives who served in the Resistance, both the "maquis" and the Free French Forces.

While completing his French military service, he was assigned to the Press Service of the French Prime Minister where he developed further interest in the study of diplomatic and military history. Building on a Master's Degree in History from the Université de Haute-Bretagne, Dr. Le Roy attended the University of Kentucky where he earned another Master’s Degree in 1989 and his Ph.D. in 1997. To read Dr. Le Roy's complete biography, click here.

Wednesday, January 31:

Dr. Erwin F. Erhardt, III

Professor of History and Political Economy at Thomas More College in Crestview Hills, Kentucky, Dr. Erhardt's research centers on the British government's domestic film propaganda efforts during World War II. Erhardt's doctoral dissertation War Aims for the Workforce: British Workers Newsreels during the Second World War, was the first in-depth look at the newsreels produced by the British-Warwork News and Worker and the Warfront and shown in war related factories though the duration of the conflict.

In addition to reviewing books for the journal Film and History on a regular basis, he is an active presenter at national and international conferences, and a member of The International Association of Media and Historians, The Film and History League, The Economic History Association, and the Indiana Association of Historians. In 2004, Dr. Erhardt was appointed Associate Director of the Centre for Evacuee and War Child Studies at the University of Reading, U.K.; and in 2006 was awarded membership in the Council for European Studies at Columbia University.

Born on October 20, 1917 in Alsatian region of France, Melville died of a heart attack at the young age of 55 on August 2, 1973.

Jean-Pierre Melville (bio here) is generally regarded as the godfather of French New Wave (Nouvelle Vague) film, paving the way for such luminaries as François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Claude Chabrol, Éric Rohmer, Louis Malle, Agnes Varda, and others.

Later generations of filmmakers, such as John Woo, Quentin Tarantino, Michael Mann, Volker Schlöndorff, Martin Scorsese, Robert Altman, Francis Ford Coppola, Brian De Palma and Roman Polanski have pointed to Melville as a key influence.

If a man's legacy is best measured not only by its quality but by the respect of his colleagues, Jean-Pierre Melville's contribution to cinema surely ranks with the greatest.

FILMOGRAPHY (14 titles)

Un Flic (Dirty Money), 1972

Le Cercle Rouge (The Red Circle), 1970

L' Armée des ombres (Army of Shadows), 1969

Le Samouraï (The Godson), 1967

Le Deuxième souffle, 1966

L' Aîné des Ferchaux, 1963

Le Doulos (The Finger Man), 1962

Léon Morin, Prêtre (Leon Morin, Priest, aka The Forgiven Sinner), 1961

Deux hommes dans Manhattan (Two Men in Manhattan), 1959

Bob Le Flambeur (Bob, The High Roller), 1955

Quand Tu Liras Cette Lettre (When You Read This Letter), 1953

Les Enfants terribles, 1950

Le Silence de la Mer (The Silence of the Sea), 1949

ON THIS PAGE: |

Advance Tickets |

Post-Film Discussion |

Filmography |

Trailers |

Ebert Essay |

Film Reviews |

The Director talks about the Film & the Resistance |

as one of the

TOP FIVE FILMS

of 2006!!

ARMY OF SHADOWS, Jean-Pierre Melville's poignant examination of what it means to love your country, reveals a slice of history where true patriotism was a gritty, lonely, perilous and often futile duty embraced by plain-spoken, ordinary people.

Melville's New Wave directorial style delivers a tense, understated epic imbued with the hard, cold realities faced by the Resistance in Occupied France — providing moral and intellectual gravitas without gratutitous fluff or use of war movie clichés.

Roger Ebert's excellent essay, which follows below, catalogs many of the extraordinary cinematic and historical elements which make this film a "must see," not the least of which is Melville's own service in the Resistance.

click here to listen to the film review on WVXU 91.7 FM, Cincinnati

click here to listen to the film review on WVXU 91.7 FM, Cincinnati

Jean-Pierre Melville's "Army of Shadows" is about members of the French Resistance who persist in the face of despair. Rarely has a film shown so truly that place in the heart where hope lives with fatalism. It is not a film about daring raids and exploding trains, but about cold, hungry, desperate men and women who move invisibly through the Nazi occupation of France. Their army is indeed made of shadows: They use false names, they have no addresses, they can be betrayed in an instant by a traitor or an accident. They know they will probably die.

This is not a typical war film. It is about a state of mind. Under the Vichy government of the World War I hero Petain, France officially permitted the Nazi occupation. Most Frenchmen accepted it as the price of immunity from German armies. DeGaulle runs the Free French movement from London but is a voice on the radio and commands no troops -- none except for those in the Resistance, who pose as ordinary citizens, lead two lives, spy on the Germans, provide information to the Allies and sometimes carry out guerrilla raids against the enemy.

Many films have shown such actions. Melville, who was himself a member of the Resistance, is not interested in making an action film. Action releases tension and makes it external. His film is about the war within the minds of Resistance members, who must live with constant fear, persist in the face of futility, accept the deaths of their comrades and expect no reward, except the knowledge that they are doing the right thing. Because many die under false names, their sacrifices are never known; in the film, two brothers never discover that they are both in the Resistance, and one dies anonymously.

As one of his films after another is rediscovered, Melville is moving into the ranks of the greatest directors. He was not much honored in his lifetime. We now know from his gangster film "Bob le Flambeur" (1955) that he was an early father of the New Wave -- before Godard, Truffaut, Malle. He used actual locations, dolly shots with a camera mounted on a bicycle, unknown actors and unrehearsed street scenes, everyday incidents instead of heightened melodrama. In "Le Samourai" (1967), at a time when movie hit men were larger than life, he reduced the existence of a professional assassin (Alain Delon) to ritual, solitude, simplicity and understatement. And in "Le Cercle Rouge" (1970), he showed police and gangsters who know how a man must win the respect of those few others who understand the code. His films, with their precision of image and movement, are startlingly beautiful.

Now we have the American premiere of perhaps his greatest film. When "Army of Shadows" was released in 1969, it was denounced by the left-wing Parisian critics as "Gaullist," because it has a brief scene involving DeGaulle and because it involves a Resistance supporting his cause; by the late 1960s, DeGaulle was considered a reactionary relic. The movie was hardly seen at the time. This restored 35mm print may be 37 years old, but it is the best foreign film of the year.

It follows the activities of a small cell of Resistance fighters based in Lyons and Paris. Most of them have never met their leader, a philosopher named Luc Jardie (Paul Meurisse). Their immediate commander is Philippe Gerbier, played by Lino Ventura with a hawk nose and physical bulk, introspection and implacable determination. To overact for Ventura would be an embarrassment. Working with him is a woman named Mathilde (Simone Signoret), and those known as Francois (Jean-Pierre Cassel), Le Masque (Claude Mann) and Felix (Paul Crauchet).

"Does your husband know of your activities?" Mathilde is asked one day. "Certainly not. And neither does my child." Signoret plays her as a mistress of disguise, able to be a dowdy fishwife, a bold whore, even a German nurse who with two comrades drives an ambulance into a Nazi prison and says she has orders to transport Felix to Paris. The greatness of her deception comes not as she impersonates the German-speaking nurse, but when she is told Felix is too ill to be moved. She instantly accepts that, nods curtly, says "I'll report that," and leaves. To offer the slightest quarrel would betray them.

The members of this group move between safe houses, often in the countryside. When they determine they have a traitor among them, they take him to a rented house, only to learn that new neighbors have moved in. They would hear a gunshot. A knife? There is no knife. "There is a towel in the kitchen," Gerbier says. We see the man strangled, and rarely has an onscreen death seemed more straightforward and final.

To protect the security of the Resistance, it is necessary to kill not only traitors but those who have been compromised. There is a death late in the film that comes as a wound to the viewer; we accept that it is necessary, but we do not believe it will happen. For this death of one of the bravest of the group, the leader Luc Jardie insists on coming out of hiding because the victim "must see me in the car." That much is owed: respect, acknowledgement and then oblivion.

There are moments of respite. Airplanes fly from England to a landing field on the grounds of a Baron (Jean-Marie Robain) to exchange personnel and bring in supplies and instructions. Gerbier and Jardie are taken to London for a brief ceremony with DeGaulle and see "Gone With the Wind." Then they are back in France.

Yes, there are moments of excitement, but they hinge on decisions, not actions. Gerbier at one point is taken prisoner and sent to be executed. The Nazis march their prisoners to a long indoor parade ground. Machine guns are set up at one end. The prisoners are told to start running. Anyone who reaches the far wall without being hit will be spared -- to die another day. Gerbier argues with himself about whether he should choose to run. That is existentialism in extremis.

Because he worked in the Resistance (and because he was working from a well-informed 1943 Joseph Kessel novel), Melville knew that life for a fighter was not a series of romantic scenes played in trench coats, but ambiguous everyday encounters that could result in death. After Gerbier escapes from Gestapo headquarters, he walks into a barber shop to have his mustache removed. The barber has a poster of Petain on his wall. Not a word is said between the two men. A sweating man at night who wants his mustache removed is a suspect. As Gerbier pays and readies to leave, the barber simply hands him an overcoat of another color.

Such a moment feels realistic, and is based on a real event. But "I had no intention of making a film about the Resistance," Melville told the interviewer Rui Nogueira. "So with one exception -- the German occupation -- I excluded all realism." The exploits of his heroes are not meant to reflect real events so much as to evoke real states of mind. The one big German scene is the opening shot, of German troops marching on the Champs-Elysees. It is one of the shots he is proudest of, Melville said, and to make it he had to win an exemption from a law that prohibited German uniforms on the boulevard.

How did Resistance fighters feel, risking their lives for a country that had officially surrendered? What were their rewards? In 1940, Melville says, the Resistance in all numbered only 600. Many of them died under torture, including Jean Moulin, the original of Luc Jardie. Kessel: "Since he was no longer able to speak, one of the Gestapo chiefs, Klaus Barbie, handed him a piece of paper on which he had written, 'Are you Jean Moulins?' Jean Moulin's only reply was to take the pencil from Colonel Barbie and cross out the 's'." By Roger Ebert / May 21, 2006

|

ARMY OF SHADOWS metascore = 99 – metacritic.com the highest score of all films currently in wide or limited release TomatoMeter = 97% Fresh – Rotten Tomatoes “A rare work of art that thrills the senses and the mind… Worthy of that overused superlative MASTERPIECE! – Manohla Dargis, NEW YORK TIMES " FOR THE FIRST, AND MAYBE THE ONLY, TIME THIS YEAR, YOU ARE IN THE HANDS OF A MASTER. Lovers of cinema should reach for their fedoras, turn up the collars of their coats, and sneak to this picture through a mist of rain… ” – Anthony Lane, THE NEW YORKER “A STUNNING LOST MASTERPIECE! ... An expert mix of political intrigue and explosive action!” – Joshua Rothkopf, TIME OUT NEW YORK "A LOST MASTERPIECE... NOT JUST ONE OF THE GREAT FILMS OF THE 60s, BUT ONE OF THE GREAT FILMS - PERIOD. The chance to discover it at the beginning of the 21st century, in an era when we think we've seen it all, is an unquantifiable privilege!” – Stephanie Zacharek, SALON.COM " Has more to tell us about the internal toll of war and taking a stand than anything Hollywood has produced! – Jami Bernard, NY Daily News “As arguably the most famous French film never to be distributed in the U.S., Jean-Pierre Melville's 1969 "Army of Shadows" has long had a special mystique, and its debut here after 37 years of waiting has to be considered one of the movie year's major events. This is particularly so since it more than lives up to its reputation. ” – William Arnold, SEATTLE POST-INTELLIGENCER A TAUT TALE OF INTRIGUE AND DARING! A KNOCKOUT CAST! It isn’t clear why it has taken so long for Army of Shadows to reach our shores. But why ask questions? Just be thankful.” – V.A. Musetto, NEW YORK POST "Making its long delayed American debut in a crisply restored print overseen by original cinematographer Pierre Lhomme, Jean-Pierre Melville's Army of Shadows is a towering achievement that makes other films look downright puny in comparison." –Timothy Knight, REEL.COM “A RESTORATION OF BEAUTY THAT DESERVES TO BE SEEN!” – Stanley Kauffmann, THE NEW REPUBLIC “MELVILLE’S SIGNATURE WORK” – Amy Taubin, Film Society of Lincoln Center “A FILM TO BE SEEN AND SAVORED!” – Andrew Sarris, NEW YORK OBSERVER "ONE OF MELVILLES'S GREATEST!" "... the images of cinematographer Pierre Lhomme are as subtly hued as a 19th Century color engraving." – Richard Schickel, TIME " – Boxoffice Magazine “THE BEST FOREIGN FILM OF THE YEAR” – Roger Ebert, CHICAGO SUN TIMES “A+ ! A MASTERPIECE! ROCK HARD GREATNESS!” Michael Sragow, BALTIMORE SUN “EXTRAORDINARY! My greatest movie treat and surprise this year” – David Ansen, NEWSWEEK “AN EVENT! PERSONAL AND POWERFUL!” – Ty Burr, Boston Globe “A CAUSE FOR CELEBRATION!” – James Verniere, Boston Herald “ A GREAT FILM…MELVILLE’S BEST… – Jonathan Rosenbaum, CHICAGO READER “A MASTERPIECE…SUPERB… an undoubted labor of love…classically constructed and immaculately shot” – Michael Wilmington, CHICAGO TRIBUNE “Masterfully made, with no detail unattended” – Kenneth Turan, LA TIMES New york post >>> “ – BOSTON GLOBE “10 OUT OF 10! A MASTERPIECE OF WORLD CINEMA!” – BOSTON GLOBE AGAIN Steven Rea, PHILADELPHIA INQUIRER Jack Garner, ROCHESTER DEMOCRAT AND CHRONICLE “ Jeff Shannon, SEATTLE TIMES “A DAMN NEAR UNIMPEACHABLE MOVIE! Serious, complex, and relentlessly intense.” Annie Wagner, THE STRANGER " – J. Carr, AM NEW YORK "ONE OF THE TWO BEST MOVIES OF 2006 Taut, superb acting, narrative told by mood rather than action, the understated visuals, the elements of 'Army of Shadows' merge to seep in under the skin and create an unforgettable and disturbing experience." Culture Vulture "Movies don't get any better than this!" – Glenn Whipp, Los Angeles Daily News “AWESOME! A TENSE, UNDERSTATED THRILLER!” – NEW YORK MAGAZINE " – Glenn Kenny, PREMIERE |

talks about "Army of Shadows" Courtesy of Rialto Pictures. Excerpted from Melville on Melville by Rui Nogueira (New York: The Viking Press, 1971); translation revised and annotated by Bruce Goldstein (2005) When did you first read Kessel's book? I discovered Army of Shadows1 in London in I943 and have wanted to film it ever since. When I told Kessel in I968 that my old dream was going to come true at last, he didn't believe anyone could pursue an idea so tenaciously for twenty-five years. Although you’ve been very faithful to the spirit of the book, you’ve again made a very personal film. This is my first movie showing things I’ve actually known and experienced. But my truth is of course subjective and has nothing to do with actual truth. With the passing of time we’re all inclined to recall what suits us rather than what actually happened. The book written by Kessel in the heat of the moment in 1943 is necessarily very different from the film shot cold by me in 1969. There are many things in the book -- wonderful things -- that are impossible to film now. Out of a sublime documentary about the Resistance, I’ve created a retrospective reverie, a nostalgic pilgrimage back to a time that profoundly marked my generation. On October 20, 1942, I was twenty-five years old. I’d been in the army since the end of October 1937. Behind me were three years of military life (one of them during the war) and two in the Resistance. That leaves its mark, believe me. The war years were awful, horrible and . . . marvelous! So the quotation from Georges Courteline2, which opens Army of Shadows, is a reflection of your own feelings: “Unhappy memories! Yet be welcome, for you are my distant youth.” Precisely. I love that phrase and I think it's extraordinarily true. I suffered a lot during the first months of my military service, and I thought it hardly possible that a man as witty, intelligent and sensitive as Courteline could have written Les Gaîtés de l'Escadron3, but of course he too had been very unhappy during his service. Then one day, thinking over my own past, I suddenly understood the charm that “unhappy memories” can have. As I grow older, I look back with nostalgia on the years from 1940 to 1944, because they’re part of my youth. Army of Shadows is considered a very important book by members of the Resistance. Army of Shadows is the book about the Resistance: the greatest and the most comprehensive of all the documents about this tragic time in the history of humanity. But I had no intention of making a film about the Resistance. So with one exception -- the German occupation -- I excluded all realism. Whenever I saw a German I always used to think, “Whatever happened to all those Teutonic Aryan gods?” They weren't these mythical blond, blue-eyed giants; they looked very much like Frenchmen. So in the movie I ignored the stereotype. Did you have a technical adviser for the German uniforms? I saw to everything myself with the assistance of my costume designer, Madame Colette Baudot, who had done a great deal of research on the subject. One day, while we were filming the shooting range sequence, the French army captain serving as technical advisor told me that there was something wrong with the SS uniforms. So I summoned Mme. Baudot and the captain said to her, “I’m from Alsace, Madame, and during the war I was forcibly enrolled in the SS. So I can assure you that an SS member always wore an armband with the name of his division on his left arm . . .” “No, sir,” Mme. Baudot replied, “You must have belonged to an operational division; the SS in the film are from a depot division.” And the captain had to admit she was right. Some critics in France accused you of presenting the Resistance workers as characters from a gangster film. It's absolutely idiotic. I was even accused of having made a Gaullist film! It's absurd how people always try to reduce to its lowest common denominator a film which wasn't intended to be abstract, but happened to turn out that way. Well, hell! I wanted to make this movie for twenty-five years and I have every reason to be satisfied with the result. The Resistance people themselves like the film very much, don't they? Yes, I’ve had wonderful letters, and when I arranged a private screening for twenty-two of the great men of the Resistance, I could see how moved they were. They were all Gerbiers, Jardies, Felixes. "As leader of the Combat movement"4, Henri Frenay told me, "I was obliged to return to Paris in December 1941, even though I had no wish to see the city under occupation. I got out of the Métro at the Etoile station, and as I was walking towards the exit I could hear the sound of footsteps overhead . . . it was a curious feeling keeping in step with them. When I came out on the Champs-Elysées I saw the German army filing past in silence, then suddenly the band struck up . . . and you reconstructed the scene for me in the first shot of your film!" For that scene, you know, I used the sound of real Germans marching. It's inimitable. It was a crazy idea to want to shoot this German parade on the Champs-Elysées. Even today I can't quite believe I did it. No one managed it before me, not even Vincente Minnelli for The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse5, because actors in German uniform had been banned from the Champs-Elysées since the First World War. One German was anxious to buy the footage from me at any price, because all they have in Germany is a black and white version of the parade. To do this shot, which may well be the most expensive in the history of French cinema -- it cost twenty-five million Old Francs6 -- I was first allowed to rehearse on Avenue d'Iéna. At three o'clock in the morning, with all traffic stopped and the Avenue lit entirely by gas lamps, men in uniform began to march past. It was a fantastic sight. Wagnerian. Unfilmable. I swear to you that I was overwhelmed. Then I was afraid . . . I began to wonder how it would go at six in the morning when I was shooting on the Champs-Elysées. You know, of all the shots I’ve done in my life, there are only two I'm really proud of: this one, and the nine-minute, thirty-eight-second shot in Le Doulos7. Where did you shoot the opening concentration camp scenes? In a former concentration camp which was completely in ruins and which I partially reconstructed for the film. Alongside this old camp there was another one, brand new, clean . . . waiting. It had been built two years before. All over the world there are camps like this one. It's fantastic. Terrifying. The Commandant of the camp is physically very different from the one Kessel describes in his book. Yes, mainly because I didn't want him to be unsympathetic. I made him a rather dry character, wearing the Pétain insignia, La Francisque. The emblem of the Fascist Party, in other words. Why in the film, unlike the book, are Luc Jardie and his brother Jean-François each unaware of the other's clandestine activities? I wanted to avoid melodrama. You don't see it? Perhaps you’re right. But go and see Army of Shadows at your local cinema. The moment the big boss comes down the ladder into the submarine and they realize he’s Jean-François's brother, the audience can't help going “Aaaahhh!” The two brothers' failure to meet is made all the more remarkable by the fact that Fate is shuffling the cards for all time: shot under a false name by the Gestapo, Jean-François will die without ever knowing that Saint-Luc is the head of the Resistance, and Saint-Luc will never discover what happened to his brother. The circumstances make the disappearance of Jean-François all the more tragic. Why, in the film, does Jean-François send the Gestapo the anonymous letter denouncing himself? This is one of those things I never explain, or don't explain enough. When Felix meets Jean-François in Marseilles, he says, “Well, still enjoying baraka?” When a man has baraka -- a divine grace bringing good fortune, according to the Arabs -- he feels immune to adversity. Jean-François isn’t afraid to send the letter which will mean his arrest because he’s convinced he’s got enough baraka to save Felix and to get away himself. But he’s got only one cyanide pill… the one he gives to Felix. When Jean-François goes to see Saint-Luc, they have their meal in that sort of glass cage installed in the middle of the library . . . There was no coal left during the war, and fuel oil wasn't used for heating in Paris. So apartments were freezing cold, especially in old houses with huge rooms; and people built these little wooden living spaces to go inside rooms, where they could eat or read and be more or less sheltered. You can't imagine what life in France was like at that time. People often slept fully dressed, shoes and socks included, because there was nothing you could do about the cold. Things weren't much better where food was concerned. Hunger became an obsession. You thought of nothing else. I can still remember the indescribable joy I experienced one day when I managed to make a sort of sandwich with lard and garlic. In the mornings, to get the circulation going, we would drink a kind of old sock juice made out of roasted peas. Because I didn't want to make a picturesque film about war, I didn't go into any of these details. As the story proceeds, my personal recollections are mingled with Kessel's, because we lived the same war. In the film, as in the book, Gerbier represents seven or eight different people. The Gerbier of the concentration camp is my friend Pierre Bloch, General de Gaulle's former Minister. The Gerbier who escapes from Gestapo Headquarters at the Hotel Majestic in Paris is Rivière, the Gaullist Deputy. As a matter of fact it was Rivière himself who described this escape to me in London. And when Gerbier and Jardie are crossing Leicester Square with the Ritz Cinema8 behind them advertising Gone With the Wind, I was thinking of what Pierre Brossolette9 said to me in the same circumstances: “The day the French can see that film and read the Canard Enchainé10 again, the war will be over." Why did you remove all the details explaining why the young man, Dounat, becomes a traitor? To explain them would have been to detract from the idea of what a betrayal means. Dounat was too weak, too fragile . . . he reminds me a little of the young liaison officer -- he was fifteen -- we had at Castres for the Combat movement. One day I had been warned by Fontaine, the Political Commissioner for Vichy, that the Gestapo was preparing a raid, and I sent him to warn the Resistance group at Castres. Although he assured me he was carrying no compromising papers, a sort of instinct made me search him and I found a notebook full of addresses. A few moments later he got himself arrested by the Germans. Despite his position, Commissaire Fontaine was a genuine Resistant. Later, he too was arrested. He was deported and never came back. What did you do during the war before you went to London? I was a sub-agent of BCRA11 and also a militant with Combat and Libération. Then I went to London. Later, on March 11, 1944, at five o'clock in the morning to be precise, I crossed the Garigliano below Cassino with the first wave. At San Apollinare we were filmed by a cameraman from the U.S. Army Signal Corps. I remember hamming it up when I realized we were being filmed. There were still Germans at one end of the village, and Naples radio was playing Harry James's Trumpet Rhapsody. I was also among the first Frenchmen to enter Lyons in uniform. Do you remember the spot where the scene between Gerbier and Mathilde takes place, beside the pigeon house? It was there, on that little Fourvière promontory belonging to the bishopric, that I arrived in a jeep with Lieutenant Gérard Faul. Lyons lay at our feet still full of Germans. We left that same evening after installing an observatory on Fourvière's little Eiffel Tower . . . When I think of everything that happened in those days, I'm amazed that the French don't make more films about the period. Do you know when I saw Faul again? One Sunday morning in February 1969: the day I had the German army marching through the Arc de Triomphe. When the scene was in the can I went to the Drugstore des Champs-Elysées with Hans Borgoff, who had been the administrator of “Gross Paris” 12 during the four years of the Occupation, and whom I had brought from Germany to come and help me shoot this scene. While I was breakfasting with the man who used to march every day at the head of the German troops, I recognized a youthful old man sitting nearby: it was Lieutenant Faul, the man I had fought under in Italy and in France. Twenty-five years later the wheel had come full circle. Why did you interpolate the scene where Luc Jardie is decorated in London by General de Gaulle? Because in Colonel Passy's13 memoirs there’s a chapter about the Compagnon de la Libération insignia being awarded to Jean Moulin, and Luc Jardie is based, among others, on Jean Moulin14. I also thought it would be interesting to show how de Gaulle decorated members of the Resistance in his private apartments in London so as not to jeopardize their return to France. Does the hotel room in London mean something particular to you? It's an exact replica of the hotel room given to every Frenchman who came to London on business concerning the Resistance. Every time I meet a member of the Resistance, he asks how I knew what his room was like. You end the film with a post-script telling of the deaths of the four leading characters. Is that what actually happened? Of course. Like Luc Jardie, Jean Moulin died under torture after betraying one name: his own. Since he was no longer able to speak, one of the Gestapo chiefs, Klaus Barbie, handed him a piece of paper on which he had written “Are you Jean Moulins?” Jean Moulin's only reply was to take the pencil from Colonel Barbie and cross out the “s.” A lot of people would have to be dead before one could make a true film about the Resistance and about Jean Moulin. Don't forget that there are more people who didn't work for the Resistance than people who did. Do you know how many Resistants there were in France at the end of 1940? Six hundred. It was only in February or March 1943 that the situation changed, because the first maquis 15 date from April 1943. And it was the proclamation by Sauckel16 about sending young people to Germany that made a lot of people prefer to go underground. It was not a matter of patriotism. How did Kessel react to your film? Kessel's emotion after the first screening of Army of Shadows is one of my most treasured memories. When he read the words telling of the deaths of the four characters, he couldn't stop himself from sobbing. He wasn't expecting those four lines which he hadn't written and which I hadn't put into the script. Do you think the film was well received in official circles? I don't know. I was at a screening at the Ministry of Information before an audience which included everybody who was anybody in the Parisian smart set. Among the two hundred people present there was only one Resistant, and he was the only one to remain transfixed in his seat after the screening. It was Friedman, the man who, one night in April I944, killed Philippe Henriot17 at the Ministry of Information. Do you remember the moment in Le Deuxième Souffle18 when Lino Ventura crosses the railway line after the hold-up? When we shot that scene, Lino said to me, “I've got it, Melville. Today I am Gu!” “No,” I told him, “today you are Gerbier!” It took me nine years to persuade him to accept the role. When we shot the scene in Army of Shadows where he crosses the railway line in the early morning, we hadn't been on speaking terms for some time, but I am sure that at that moment he was thinking of what happened at Cassis railway station while we were filming Le Deuxième Souffle. FOOTNOTES 1 Army of Shadows, by Joseph Kessel (1944, Alfred A. Knopf). 2 Courteline (1858-1929) was a French dramatist and novelist known for his satiric wit. 3 A satire on military life, published in 1886. 4 A resistance group founded by Henri Frenay (1905-1988) and others; Frenay also edited an underground newspaper by that name. Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre were also Combat members. 5 Released by MGM in 1962 6 The equivalent of 250,000 New Francs; approximately $50,000 7 Le Doulos (1962), a gangster film starring Jean-Paul Belmondo; the shot referred to by Melville is a 360-degree pan in a room full of reflecting glass. Le Doulos will be re-released by Rialto Pictures next year. 8 The Ritz was an actual London cinema, which had the distinction of playing Gone With the Wind for most of the war years (July 11, 1940 through June 8, 1944), the second longest run in a single West End cinema. Melville was lucky to film the Ritz marquee during GWTW’s 1969 reissue. 9 Pierre Brossolette (1903-1944) was a socialist, journalist and member of the Resistance; captured by the Germans, he jumped to his death from Gestapo headquarters. 10 Literally, “Chained Duck,” a French satirical magazine still published today. 11 Bureau Central de Renseignements et d'Action, the Free French military intelligence unit. 12 “Gross Paris” was the German administrative designation for the greater Paris region. 13 “Coloney Passy” was the pseudonym for André Dewavrin (1911-1998), head of the BCRA and one of the chief architects of the French Resistance movement; Passy plays himself in Army of Shadows. 14 Moulin (1899-1943) was a legendary Resistance fighter. He was captured and tortured to death by Klaus Barbie. Moulin’s ashes were transferred to the Panthéon in 1964. 15 The predominantly rural guerrilla bands of the Resistance 16 Fritz Sauckel (1894-1946), a senior German government official in charge of forced labor. He was convicted at the Nuremburg Trials for crimes against humanity and hanged. 17 Henriot was the Vichy government's Secretary of State for Information and Propaganda. 18 Melville crime thriller released in 1966; Ventura played a character called Gustave Minda, nicknamed “Gu”. |