DISCUSSION LEADER

THOR JACOBS

We are delighted to have Thor Jacobs as our discussion leader for IRAQ IN FRAGMENTS. Thor shares the following about his background and familiarity with Iraq and the Middle East:

"I have been fascinated with international relations and foreign policy my entire adult life and have studied the Middle East in particular at great length. My interest may have been ignited when as three year old, I moved with my family to Baghdad, Iraq in 1961 where my father, Dr. James Jacobs, took up residence to work as a UN consultant to the Iraqi Ministry of Education.

"I have been fascinated with international relations and foreign policy my entire adult life and have studied the Middle East in particular at great length. My interest may have been ignited when as three year old, I moved with my family to Baghdad, Iraq in 1961 where my father, Dr. James Jacobs, took up residence to work as a UN consultant to the Iraqi Ministry of Education.

"My father returned to Baghdad in 1976 serving an additional four months before being summoned home in order to take the helm as Superintendent of the Cincinnati Public Schools. A post he held with great distinction until his untimely passing in 1985.

"A year after I graduated from college, I moved to the United Arab Emirates to take a job as the manager of a small import-distribution company outside of Dubai. Technically an Arab country, 90% of the people who lived in the UAE where foreigners of every conceivable stripe.

"In the mid-1990s I started traveling a lot for both business (mostly Latin America) and pleasure including all over the Middle East. I spent a significant amount of time in cities like Cairo, Jerusalem, Amman, Istanbul and Damascus. I also explored the countries of Lebanon, Bahrain, Turkey and Morocco.

"In 1998, I moved to Beirut, Lebanon where I spent the better part of the next three years earning a Masters Degree in International Relations from the most storied university in the Middle East - The American University of Beirut. It allowed me to travel the Mediterranean region ever the more including the likes of Spain, Greece, France and Italy.

"In addition to my living and travel experiences, I have read well over a hundred books on the subjects of political science, foreign policy, the Middle East, world history, religion and terrorism. I subscribe to the Economist, Foreign Policy magazine and National Geographic, not to mention read all sorts of international newspapers on-line. I am also a member of the Foreign Policy Leadership Council of Cincinnati (FPLC).

"My formal education includes the following:

BSBA - The Ohio State University - Economics and International Business -1981

MBA - University of Cincinnati - Marketing - 1986

MA - The American University of Beirut - International Relations - 2001"

CRITICAL RESPONSE

"Grade "A" Longley looks and listens, with nonjudgmental sensitivity, as Sunni, Shiite, and Kurdish Iraqis explain their colliding, intractable, invaded worlds, and their rising frustrations. He lets people be people, not position-holders. The calm poetry of the cinematography offsets the mess of the politics to stunning effect."

-- Lisa Schwarzbaum, Entertainment Weekly

"Iraq in Fragments is astonishing, both in its beauty and its breadth. While Longley's use of jump-cuts and visual collages has the feel of an art piece, it is the director's contact with his subjects that is truly astounding."

-- Dan Glaister, The Guardian

"Not just another Iraq war doc...Whether or not James Longley's boldly stylized reportage breaches public indifference, its enduring value is assured: When the war is long gone, this deft construction will persist in relevance, if not for what it says about the mess we once made, then as a model of canny cinematic construction."

-- Nathan Lee, The Village Voice

"The movie is more than the sum of its fragments. The montages are intense, the images ravishing. The movie is tactile. When you finally feel this place, you understand just how little you understand."

-- David Edelstein, New York Magazine

"Viewed by many as the ultimate cinematic statement on Iraq...Mr. Longley is both a tremendously skilled filmmaker and a brave one, having spent two and a half years gathering his footage. Iraq in Fragments is a valuable document and, given the security situation, perhaps the last, and the most enduring, of its kind."

-- New York Sun

"Terrific...something close to a documentary masterpiece."

-- Andrew O'Hehir, Salon

"this one demands to be seen...mesmerizes with its insight and, rarer still, its beauty."

-- Kenneth Turan, LA Times

"In beautifully shot, almost poetic images, it takes us inside this fractured country, letting us feel what its like from the inside from three points of view--Sunni, Shiite and Kurd. ... A fascinating glimpse of an Iraq the mass media never shows us, the movie is a quiet revelation."

-- David Ansen, Newsweek

"Iraq in Fragments is the latest entry in the crowded field of documentaries from that war. It is also one of the best, partly because it is more concerned with exploring daily life and individual destinies than with articulating a position. ... Whether you think the war is right or wrong, Iraq in Fragments is a necessary reminder of just how painful and complicated it is."

-- A.O. Scott, The New York Times

"... a one-man production of startling audacity and aesthetic provocation. ... if Longley's astonishing feat of poetic agitation has a precedent in the entire history of documentary, I'm not aware of it."

-- Rob Nelson, The Village Voice

"Stands head and shoulders above an overcrowded field of documentaries about the Iraq war...This visually sumptuous movie richly deserves the cinematography, editing and directing prizes it carried off at Sundance last January."

-- Ella Taylor, LA Weekly

"James Longley's mesmerizing Iraq in Fragments shakes off the oversaturated video vocabulary that has defined media coverage of the war-torn country and brings a cinematic beauty, both terrifying and ethereal"

-- Stephen Garret, Indiewire

"The first documentary about the war in Iraq to be made by a real filmmaker...Longley has a gift for intimacy and an eye for vagrant touches of beauty everywhere"

-- The New Yorker

"Longley's sensitive eye for imagery and graceful camerawork ... gives the film a beauty rarely seen ..."

-- Seattle Post-Intelligencer

"highly recommended; a beautifully shot, fascinating and informative portrait ... a searing vision of this historical miasma."

-- Time Out London

"an Iraq that you haven't likely seen before ... stunning"

"Iraq in Fragments is an in-depth marvel"

-- New York Magazine

"[Iraq In Fragments is] an invitation to look again and afresh at a country many Americans may be tired of thinking about, and to be reminded of the complicated human reality underneath the politics."

-- New York Times

"a masterpiece ..."

-- Noel Murray, The Onion

"Differs dramatically from the documentaries about the occupation told from the American point of view...Not only does Longley capture the literal point of view, he also bathes many of his shots in a dark, golden light that mirrors the shadowy threat posed by the country's violent, unsettled state."

-- Eric Monder, Film Journal

"Iraq in Fragments is a beautifully filmed biography of a country on the verge of civil war."

-- Peter Byck, Lousiville Courier-Journal

"A patient, lyrically photographed, closely observed meditation that pays calm attention to aspects of Sunni, Shiite, and Kurdish daily life."

-- Entertainment Weekly

"a rarity ... an extraordinary journalistic coup"

-- Film Comment

"***** (5 Stars - Perfect!) A raw and powerful film that demands to be seen!"

-- Phil Hall, Film Threat

"The [San Francisco International Film] festival's best doc ... stunning"

-- Gregg Rickman, SF Weekly

"Magnificent" and "The best movie yet about the Iraq war...Stunningly lyrical"

-- The Stranger

"Not a moment from these Sunni, Shiite and Kurdish daily lives is familiar from U.S. news programs, and it's all eye-opening."

-- In These Times

"a visually startling, patiently observed and deeply humanist film"

"the most lacerating and complex American doc so far about the war Over There."

-- Eye Weekly

"beautifully shot, well-edited and gives you a picture of Iraq that you've never seen before."

-- John Powers, Fresh Air

"It only takes a few minutes of watching Iraq in Fragments to recognize that the film stands apart from the Iraqumentary pack: dazzling cinematography in place of the dull visuals of the evening news, slice-of-life narration instead of talking heads. Divided into three sections, director James Longley's reportage shows us the everyday chaos in Baghdad and beyond with dramatic vividness — a vividness that, if nothing else, makes us realize how degraded most of the imagery we receive from Iraq is at the moment."

-- Max Goldberg, San Francisco Bay Guardian

"Compelling...indispensable art"

-- Stuart Klawans, The Nation

|

Director James Longley's Production Notes

Pre-Production

One rainy Seattle evening in the spring of 2002 I was fielding questions at the premiere of my first feature documentary, GAZA STRIP. Someone finally asked the question that always gets asked: "What are you going to make next?" Without thinking I replied that I would make a documentary about Iraq.

At the time I didn't know much about Iraq; I hadn't even the faintest idea of how to get there, let alone make a film there. And yet, by September I found myself in a car with a collection of journalists and peace activists, crossing the western Iraqi desert to Baghdad.

The US invasion of Iraq was still six months away but everybody could feel it coming, including the Iraqi government. As the invasion approached, the Iraqi officials became less and less interested in an independent filmmaker like me running around their country with a camera.

In their eyes, every freelance foreign journalist requiring a government minder was only taking resources away from media that mattered to their propaganda strategy. In short, I was a waste of their time. I didn't particularly care for the Baathist government - or indeed any government - and the Iraqi officials could probably tell. My entreaties for filming permissions were coldly ignored.

My second trip to Iraq, just weeks before the US invasion, met with even less success. Trying to get filming permissions in pre-war Baghdad was like trying to sweet-talk a paranoid rhinoceros. I spent one afternoon hanging out around the Baghdad office of Huda Amash, known thereafter in the US media as Dr. Germ, trying to convince her to give me a piece of paper allowing me to film during the impending war. Huda brushed off my request and sped away with her bodyguards in a white Mercedes along the Tigris. Within a month she was living in a US prison camp at the airport.

The war was only days away and I had no prospect of filming anything. My Iraqi visa expired, effectively forcing me out of the country. As I drove along the crowded streets of Baghdad toward the Jordan highway I was full of regret. The next time I saw Baghdad it might well be in ruins. I had no idea what would become of my friends in Iraq. Leaving Baghdad before the war was one of the saddest moments of my life.

The war was only days away and I had no prospect of filming anything. My Iraqi visa expired, effectively forcing me out of the country. As I drove along the crowded streets of Baghdad toward the Jordan highway I was full of regret. The next time I saw Baghdad it might well be in ruins. I had no idea what would become of my friends in Iraq. Leaving Baghdad before the war was one of the saddest moments of my life.

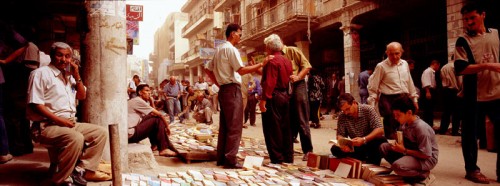

I waited out the war in Egypt, pacing distractedly back and forth across Cairo through the haze and mind-numbing traffic, watching the nightly bombing of Baghdad on television, biding my time until the Baathist regime would be overthrown and I could return to Iraq to make a film about whatever happened next.

By April 2003 I arrived back in Baghdad, this time without need of a visa or filming permissions of any kind. The Iraqi border hung open like a door off its hinges. The apparatus of state lay shattered, ministries on fire. All, that is, but the ministries of Oil and Interior. Baghdad had descended into a regime of looting, kidnappings, shootings, bombings, and a deep uncertainty about the future of the country.

Production

Suddenly the flood gates had opened. There was no government in Iraq and I could film whatever I wanted as long as I could stay alive.

My guess was that I would have about a year before either a new authoritarian government would be put in power or Iraq would descend into civil war and become too dangerous to work in. I needed to make my film while it was still possible.

I moved into a seedy apartment at the Al Dulami building in southern Baghdad with radio journalists Raphael Krafft and Aaron Glantz as roommates. Using my Iraqi expatriate contacts I found a local translator to work with and we set off together to document the country.

Part One

For my first documentary subject in Iraq I decided on an 11-year-old auto mechanic named Mohammed Haithem who lived and worked in the Sheik Omar district of Baghdad, an old neighborhood at the center of town full of small industrial shops.

Young Mohammed was looked after by his grandmother and had dropped out of school to support his family by working as a shop apprentice. Mohammed's was a very common story in Iraq, a country which has suffered decades of foolish wars, despotism and suffocating economic sanctions that weakened the social infrastructure.

Mohammed Haithem had a sort of Dickensian quality that I thought perfectly matched the Best/Worst of Times feeling in post-war Baghdad. His face spoke for him; you could tell what he was thinking without him ever saying a word.

Mohammed Haithem had a sort of Dickensian quality that I thought perfectly matched the Best/Worst of Times feeling in post-war Baghdad. His face spoke for him; you could tell what he was thinking without him ever saying a word.

Every morning for months on end I would drive out to the shop where Mohammed worked and wait around for hours, gradually becoming part of the furniture until nobody paid attention to me or my camera.

In the evenings I began to translate the material and layer it together on an Apple laptop computer, building up a picture of Mohammed and the world around him, trying to see it through his eyes.

I didn't just want to bring the viewers into Mohammed's neighborhood - I wanted to put them inside his head. I wanted them to see what he saw, hear what he heard, including the sound of his own thoughts.

To make the voice-over narration in this chapter I conducted extensive audio interviews with Mohammed, gradually working through his shyness until he was speaking in clear, complete sentences. It took about a year to reach this point; my last material of Mohammed Haithem was recorded in September of 2004.

By that time Iraqi public opinion had turned solidly against the US occupation and it was already too dangerous for a foreign filmmaker to work openly on the streets of the capital.

Part Two

By the middle of the first summer I had moved out of my gloomy apartment and into a small residential house in the middle-class Palestine Street area of Baghdad. I shared the ground floor with Nadeem Hamid, one of the Iraqi translators I was working with.

Nadeem was a 22-year-old biology student at Mustansiriya University, and had been written up by the New York Times Magazine, Fox News and the BBC for being the lead singer of an Iraqi boy-band that sang pop songs in English. It was exactly the story that the western media were looking for: young Iraqis in love with western culture, liberal and open to all ideas. By the time my documentary production finished Nadeem had left Iraq to escape a nascent civil war and persecution by a new regime of conservative Islam that the United States had helped bring to power.

Iraq had been ruled by Sunnis for hundreds of years, and suddenly the majority Shiites were sensing that their moment had arrived. I wanted to film the emergence of Iraq's Shiite power from the inside.

In August, 2003, Nadeem and I drove down to Najaf, burial place of Imam Ali and the capital of Shia Islam in Iraq. My idea was to follow a student at one of the local Shiite religious schools. Wandering through the narrow back alleys of Najaf in search of permissions, Nadeem and I soon found ourselves at the office of Moqtada Sadr.

Moqtada Sadr had inherited the followers and organization of his father, Grand Ayatollah Mohammed Sadiq al-Sadr, one of the most respected and influential religious leaders in Iraq's modern history, who had been assassinated by Saddam Hussein in 1999 for speaking out against the regime. Mohammed Sadiq al-Sadr had advocated something known as the speaking Hawza, an Iraqi nationalist political/religious philosophy that encouraged the open involvement of religious authority in political life.

Moqtada Sadr's family had been involved in routing the British colonial occupation of Iraq earlier in the 20th century, they had risen up against the dictatorship of Saddam, and now his movement was warming to a new challenge. Young Sadr wanted to push the foreign occupiers out of his country and turn Iraq into an Islamic state.

This seemed like an interesting story to document, so I began developing contacts within Sadr's organization who allowed me to film. Moqtada Sadr himself was too difficult to access, so I settled for Sheik Aws al Kafaji.

This seemed like an interesting story to document, so I began developing contacts within Sadr's organization who allowed me to film. Moqtada Sadr himself was too difficult to access, so I settled for Sheik Aws al Kafaji.

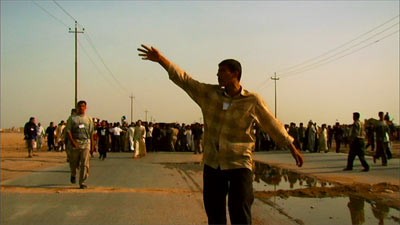

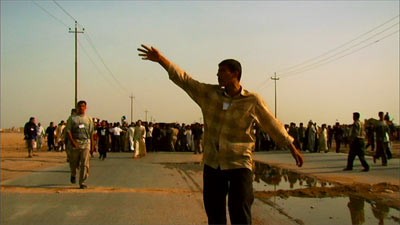

Sheik Aws, a bearded cleric of 32, was in charge of the Sadr office in Naseriyah, the fourth largest city in Iraq. Aws had been imprisoned and tortured under Saddam for defying the regime. He was genial and open, giving me far more access to his movement than I expected. I filmed political strategy meetings, rallies, marches, an alcohol raid in the local market, religious ceremonies, and endless political speeches and interviews with fighters in the Mehdi Army militia.

The only other western civilian I encountered in Naseriyah in that period was Anthony Shadid, a mild-mannered Washington Post journalist who later received the Pulitzer Prize for his brilliant reporting on Iraq. Sheik Aws was convinced that Anthony worked for the CIA, and often told me so. He also suspected that I might be CIA. It's not an accusation that one can easily disprove. The Sadr organization was deeply suspicious of foreigners, and you couldn't really blame them. I was never sure why they trusted me as much as they did.

In the early spring of 2004, riding a wave of popular sentiment, the Sadr office in Naseriyah was organizing elections. It was a full year before national Iraqi elections would actually take place, and the United States occupation authorities in Iraq were still hopeful that they could forego popular elections and install a puppet Iraqi government made up of politicians appointed indirectly by the United States. The Sadr movement's strategy was to circumvent this by pushing out US appointees through direct local elections.

This idea, combined with strong anti-occupation and anti-Israel rhetoric, made Moqtada Sadr and his movement a dangerous opponent of United States' interests in Iraq. Charges were brought against Sadr for a murder that had occurred a year before, his deputies were arrested and his Hawza newspaper was shut down by US soldiers. When Spanish troops opened fire on a Sadr demonstration in Kufa on April 4, 2004, it finally provoked an armed uprising among Sadr's followers. The uprising lasted until September and resulted in the deaths of thousands.

I arrived slightly late for the initial battle in Kufa - it had already been going on for an hour when my taxi dropped me off on the main street and sped back toward Baghdad.

The sound of automatic gunfire was all around. Hidden snipers were firing from the upper floors of buildings beside me, provoking answering fire from the Spanish base. American fighter planes circled overheard, requesting - it was later reported by UPI - permission from the Spanish to bomb the nearby teaching hospital where Sadr's fighters had taken up positions on the roof.

It was the first in a long succession of skirmishes around Najaf that eventually led to the siege of the city by US forces. I spent several months living in Najaf during the uprising, recording interviews with fighters and civilians, dreading what would happen as the tensions mounted.

The Sadr movement had taken over the Imam Ali Shrine in the center of Najaf, and also the Islamic Court building, where many of their political opponents in the city were taken and a number executed. The bodies of the hanged were adorned with handwritten signs that read "spy" and photographed for publication in the Sadr newspapers.

The Sadr movement had taken over the Imam Ali Shrine in the center of Najaf, and also the Islamic Court building, where many of their political opponents in the city were taken and a number executed. The bodies of the hanged were adorned with handwritten signs that read "spy" and photographed for publication in the Sadr newspapers.

I was also dragged to the court on one occasion along with my Iraqi translator. They accused me of filming the bodies of Mehdi Militia fighters in the Najaf cemetery, though I had intentionally left my camera in my hotel room that day, expecting trouble. "No," they insisted, "you were filming."

They had been losing large numbers of fighters due to their incredibly poor appreciation of US military tactics, and their anger made them unreasonable. The Sadrists at the Najaf Islamic Court weren't exactly the sharpest knives in the drawer to begin with. Filming in Najaf became impossible, even with signed permissions from their own leadership.

The Sadr uprising coincided with the US siege and destruction of Falluja, which was broadcast into Iraqi homes by Al Jazeera. The abuse and torture by US personnel of Iraqis at Abu Ghraib prison was also unequivocally revealed that month, further adding to the anger that was rising in the country. In an effort to contain the unrest, the United States closed down unfriendly media and handed Iraqi "sovereignty" to an interim government headed by a former CIA asset.

The situation for journalists and filmmakers working in Iraq was also growing increasingly difficult. I was forced to move out of the residential home I had shared with translator Nadeem Hamid and his family - as much for their protection as my own. An increasing number of journalists and other foreign civilians was being kidnapped and killed. I had already received several death threats, both against myself and the people I was filming.

My colleague Micah Garen, an independent filmmaker from New York, was kidnapped along with his translator by members of the Sadr movement in Naseriyah - the very place I had been filming only months before. He was accused of being a spy and threatened with execution. I used my contacts in the Sadr organization to lobby for his release via satellite phone. Through the collective efforts of his family, friends and fellow journalists Micah was released unharmed, but not before being held for 10 days in the southern marshes and paraded on TV with a gun to his head, reading a forced statement.

I decided that central and southern Iraq were no longer safe enough to film in. The risk had become too great and the work had become impossible. I filmed my last material in Baghdad in September, 2004, gathered up my clothes, hard drives, and boxes of DV tapes, and hired a taxi for northern Iraq.

Part Three

Entering Kurdish-controlled northern Iraq is like crossing into a different country. The lonely and dangerous roads north of Baghdad give way to a series of rolling hills and checkpoints. Suddenly the flags flying from rooftops display the yellow sun of Kurdistan, a non-existent country that has been waiting to be born for a hundred years.

I had been making trips northward to Iraqi Kurdistan since early in my production, exploring the cities and towns of the mountainous border regions and the low-lying grassy plains that stretch south toward Kirkuk, the disputed oil capital of northern Iraq.

I had been making trips northward to Iraqi Kurdistan since early in my production, exploring the cities and towns of the mountainous border regions and the low-lying grassy plains that stretch south toward Kirkuk, the disputed oil capital of northern Iraq.

After some searching, I had settled into a small scattering of farms and brick ovens south of Erbil, in a place known as Koretan. It's so small, it's not even found on most maps of Iraq. The locals eke a living out of wheat, tomatoes, sunflowers and bricks.

It was the brick ovens that made me stop there. Great plumes of black petroleum smoke pouring out of a featureless landscape of wheat. The brick ovens had been built by Iraqi Jews in the early 20th century. Many local farmers were the descendants of Jews who had converted to Islam. The entire region bore the marks of passing waves of religious change.

Even the name of the capital, Erbil - meaning "four gods" - dated back to Pagan times. In neighboring Mosul, 30 minutes away by car, the ruins of Sumerian civilization dating back to 5000 BC still stood. Mosul was already beyond the pale: I had filmed there several times, but by late 2004 it was already far too dangerous.

I gradually made friends with the local farmers in Koretan. Little by little, I became a regular fixture. People grew more comfortable and stopped taking notice of me. After six short months, I had achieved invisibility. Over time, I was able to film enough material to piece together a portrait of this place, these people.

After the tumultuous Shiite uprising in the south, it was important to me to ground my storytelling in northern Iraq in smaller, more personal stories. I focused on simple things: The friendship of two boys and their fathers who lived on neighboring farms. I decided that this chapter would be about fathers and sons, of the space between generations. It was a theme that echoed throughout the film.

Behind this simple story was a larger movement in the society. The Kurds were pressing for independence. Anti-Arab sentiment ran high. The Kurds were ready to go to war, if necessary, to continue their autonomy from Baghdad and solidify control over oil-rich Kirkuk, the foundation of a future independent state they hoped to build. The January 2005 elections solidified Kurdish power within the Iraqi leadership. Protesting US attacks against them, the Sunni Arabs had largely boycotted elections and remained largely outside the official politics of Iraq. The Supreme Council for Islamic Revolution in Iraq, led by the Hakim family and lobbying for a separate Shiite state in the oil-rich south, had gained dominance within the largest Shiite bloc. The fracture lines had been drawn that would permanently split Iraq into fragments.

Behind this simple story was a larger movement in the society. The Kurds were pressing for independence. Anti-Arab sentiment ran high. The Kurds were ready to go to war, if necessary, to continue their autonomy from Baghdad and solidify control over oil-rich Kirkuk, the foundation of a future independent state they hoped to build. The January 2005 elections solidified Kurdish power within the Iraqi leadership. Protesting US attacks against them, the Sunni Arabs had largely boycotted elections and remained largely outside the official politics of Iraq. The Supreme Council for Islamic Revolution in Iraq, led by the Hakim family and lobbying for a separate Shiite state in the oil-rich south, had gained dominance within the largest Shiite bloc. The fracture lines had been drawn that would permanently split Iraq into fragments.

Technical Notes

IRAQ IN FRAGMENTS was shot with Panasonic DVX-100 and DVX-100A cameras, using 24p Advanced Pulldown mode, letter-boxed. All sound was recorded on the camera.

300 hours of material were recorded in Iraq between February 2003 and April 2005 for the production. 1600 pages of typed, time-coded, translated transcripts were used in editing.

The film was edited by Billy McMillin, James Longley and Fiona Otway using Final Cut Pro software running on Apple Macintosh computers.

The film was blown up to High Definition size and color corrected at Modern Digital in Seattle.

Dolby Digital sound mixing took place at Bad Animals studios in Seattle.

File-to-Film recording was done at Alpha Cine Labs in Seattle.

About the Director

James Longley was born in Oregon in 1972. He studied Film and Russian at the University of Rochester and Wesleyan University in the United States, and the All-Russian Institute of Cinematography (VGIK) in Moscow. His student documentary, Portrait of Boy with Dog, about a boy in a Moscow orphanage, was awarded the Student Academy Award in 1994 by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

James Longley was born in Oregon in 1972. He studied Film and Russian at the University of Rochester and Wesleyan University in the United States, and the All-Russian Institute of Cinematography (VGIK) in Moscow. His student documentary, Portrait of Boy with Dog, about a boy in a Moscow orphanage, was awarded the Student Academy Award in 1994 by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

After working as a film projectionist in Washington State, an English teacher in Siberia, a newspaper copy editor in Moscow, and a web designer in New York City, James traveled to Palestine in 2001 to make his first feature documentary, Gaza Strip. The film, which takes an intimate look at the lives and views of ordinary Palestinians in Israeli-occupied Gaza, screened to critical acclaim in film festivals and U.S. theaters.

In 2002, James traveled to Iraq to begin pre-production work on his second documentary feature, Iraq in Fragments, which was completed in January 2006 and premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, where it was awarded prizes for Best Documentary Directing, Best Documentary Editing, and Best Documentary Cinematography - the first time in Sundance history a documentary has received three jury awards. Iraq in Fragments went on to win the Nestor Almendros Award at the Human Rights Watch Film Festival, the Nesnady + Schwartz Documentary Film Competition at the Cleveland Intl Film Festival, the FIPRESCI International Critics Award at Thessaloniki, and the Grand Jury Award at the Full Frame Documentary Film Festival.

James Longley's short film, Sari's Mother, premiered at the 2006 Toronto International Film Festival.

|

"I have been fascinated with international relations and foreign policy my entire adult life and have studied the Middle East in particular at great length. My interest may have been ignited when as three year old, I moved with my family to Baghdad, Iraq in 1961 where my father, Dr. James Jacobs, took up residence to work as a UN consultant to the Iraqi Ministry of Education.

"I have been fascinated with international relations and foreign policy my entire adult life and have studied the Middle East in particular at great length. My interest may have been ignited when as three year old, I moved with my family to Baghdad, Iraq in 1961 where my father, Dr. James Jacobs, took up residence to work as a UN consultant to the Iraqi Ministry of Education.

The war was only days away and I had no prospect of filming anything. My Iraqi visa expired, effectively forcing me out of the country. As I drove along the crowded streets of Baghdad toward the Jordan highway I was full of regret. The next time I saw Baghdad it might well be in ruins. I had no idea what would become of my friends in Iraq. Leaving Baghdad before the war was one of the saddest moments of my life.

The war was only days away and I had no prospect of filming anything. My Iraqi visa expired, effectively forcing me out of the country. As I drove along the crowded streets of Baghdad toward the Jordan highway I was full of regret. The next time I saw Baghdad it might well be in ruins. I had no idea what would become of my friends in Iraq. Leaving Baghdad before the war was one of the saddest moments of my life.

Mohammed Haithem had a sort of Dickensian quality that I thought perfectly matched the Best/Worst of Times feeling in post-war Baghdad. His face spoke for him; you could tell what he was thinking without him ever saying a word.

Mohammed Haithem had a sort of Dickensian quality that I thought perfectly matched the Best/Worst of Times feeling in post-war Baghdad. His face spoke for him; you could tell what he was thinking without him ever saying a word.

This seemed like an interesting story to document, so I began developing contacts within Sadr's organization who allowed me to film. Moqtada Sadr himself was too difficult to access, so I settled for Sheik Aws al Kafaji.

This seemed like an interesting story to document, so I began developing contacts within Sadr's organization who allowed me to film. Moqtada Sadr himself was too difficult to access, so I settled for Sheik Aws al Kafaji.

The Sadr movement had taken over the Imam Ali Shrine in the center of Najaf, and also the Islamic Court building, where many of their political opponents in the city were taken and a number executed. The bodies of the hanged were adorned with handwritten signs that read "spy" and photographed for publication in the Sadr newspapers.

The Sadr movement had taken over the Imam Ali Shrine in the center of Najaf, and also the Islamic Court building, where many of their political opponents in the city were taken and a number executed. The bodies of the hanged were adorned with handwritten signs that read "spy" and photographed for publication in the Sadr newspapers.

I had been making trips northward to Iraqi Kurdistan since early in my production, exploring the cities and towns of the mountainous border regions and the low-lying grassy plains that stretch south toward Kirkuk, the disputed oil capital of northern Iraq.

I had been making trips northward to Iraqi Kurdistan since early in my production, exploring the cities and towns of the mountainous border regions and the low-lying grassy plains that stretch south toward Kirkuk, the disputed oil capital of northern Iraq.

Behind this simple story was a larger movement in the society. The Kurds were pressing for independence. Anti-Arab sentiment ran high. The Kurds were ready to go to war, if necessary, to continue their autonomy from Baghdad and solidify control over oil-rich Kirkuk, the foundation of a future independent state they hoped to build. The January 2005 elections solidified Kurdish power within the Iraqi leadership. Protesting US attacks against them, the Sunni Arabs had largely boycotted elections and remained largely outside the official politics of Iraq. The Supreme Council for Islamic Revolution in Iraq, led by the Hakim family and lobbying for a separate Shiite state in the oil-rich south, had gained dominance within the largest Shiite bloc. The fracture lines had been drawn that would permanently split Iraq into fragments.

Behind this simple story was a larger movement in the society. The Kurds were pressing for independence. Anti-Arab sentiment ran high. The Kurds were ready to go to war, if necessary, to continue their autonomy from Baghdad and solidify control over oil-rich Kirkuk, the foundation of a future independent state they hoped to build. The January 2005 elections solidified Kurdish power within the Iraqi leadership. Protesting US attacks against them, the Sunni Arabs had largely boycotted elections and remained largely outside the official politics of Iraq. The Supreme Council for Islamic Revolution in Iraq, led by the Hakim family and lobbying for a separate Shiite state in the oil-rich south, had gained dominance within the largest Shiite bloc. The fracture lines had been drawn that would permanently split Iraq into fragments.

James Longley was born in Oregon in 1972. He studied Film and Russian at the University of Rochester and Wesleyan University in the United States, and the All-Russian Institute of Cinematography (VGIK) in Moscow. His student documentary, Portrait of Boy with Dog, about a boy in a Moscow orphanage, was awarded the Student Academy Award in 1994 by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

James Longley was born in Oregon in 1972. He studied Film and Russian at the University of Rochester and Wesleyan University in the United States, and the All-Russian Institute of Cinematography (VGIK) in Moscow. His student documentary, Portrait of Boy with Dog, about a boy in a Moscow orphanage, was awarded the Student Academy Award in 1994 by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.