W H A T :

W H E N :

Screenings at 7:00 pm,

doors open at 6:30 pm

W H E R E :

click for Directions & Map

T I C K E T S :

$6 tickets are ONLY available online, by phone, at the Museum, and at the door subject to availability.

ADVANCE TICKETS:

...and at these locations

($8 tix only, cash only),

click each location below for a map:

Sitwell's Coffee House

513 281 7487

Lookout Joe Coffee Roasters

513 871 8626

Shake It Music & Video

513 591 0123

The Bean Haus

859 431 2326

LEARN MORE ABOUT BALTHAZAR

BECAUSE THIS FILM is so good and so important, so much has been written about it that it is difficult to add anything new to the existing body of commentary. Indeed, many reviewers concede that doing justice to Bresson in the form of commentary, criticism, spoken tribute, or written examination is almost impossible.

Balthazar has landed on numerous 'best films ever' lists and if you are interested in critical review and analysis, several resources are listed below.

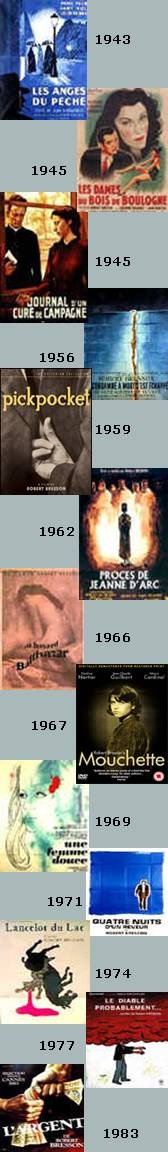

a wonderful, academically-oriented site for learning about the classics, where Bresson has his own "wing." Worth reading are the commentaries on Balthazar by Daryl Chin and Doug Cummings (the latter is found under the DVD review). Actually, everything on the site about Bresson is worth reading — he was a fascinating filmmaker and made many films.

which provides an aggregate score based on numerous professional reviewer ratings. Balthazar earned a 'fresh tomatoes' score of 100% (out of 100), with an average rating of 9.4 out of 10.

which also provides an aggregate score based on professional reviewer ratings. Balthazar earned a score of 100 (out of 100).

the Movie Review Query Engine, offering over 600,000 movie reviews and articles. The "Balthazar" page features 30+ incisively written and thought provoking reviews on the film.

with links to roughly 50 reviews and a wealth of general information about this and a gazillion other films.

this film distributor site has links to excellent Balthazar and Bresson material at the Film Forum and many other websites.

ON THIS PAGE: |

Ticket Info |

About the Film |

Synopsis |

Resources |

About the Director |

Post-Film Discussion |

Critical Acclaim |

Bresson, Balthazar and Religion |

Cast and Crew |

About Rialto Pictures |

From across America, the acclaim has been universal ...

The new release of Balthazar offers a rare chance to see this 1966 French masterpiece — the finest, most deeply personal work of a filmmaker who has been compared, justifiably, to both Dostoyevsky and Bach. ~ Chicago Tribune

The relentless commercialization of movies is understandable; people get rich off movies and more power to them. But there are other kinds of movies — those movies you carry inside you and that press on your chest — they exist nonetheless. French director Robert Bresson's 1966 film is being redistributed; there is no more important movie now in theaters. ~ L.A. Times

Au Hasard Balthazar makes large demands upon its audience, and in return confers exceptional rewards. It is the only absolutely essential moviegoing in New York. ~ New York Times

Why this film is important and why you should see it

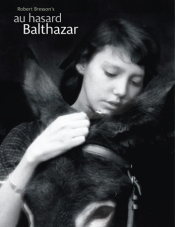

There is really no other film like Au Hasard Balthazar; it is one of the few films that truly matter. This is a film you should see on the big screen in 35mm in a movie theatre, and one you'll want to watch again, perhaps at home, as it becomes richer with repeated viewings.

What's in it for you, the viewer? This film can be seen as a simple animal fable, as Balthazar the donkey suffers nobly at the hands of his handlers. Or, it can be taken as the story of Marie, Jacques and Gerard and selected others who inhabit a rural French village, whose lives intertwine with the life of Balthazar. Indeed, this story could take place in a small Midwest farm town — you'll recognize people you know in the character types Bresson gives us.

What's in it for you, the viewer? This film can be seen as a simple animal fable, as Balthazar the donkey suffers nobly at the hands of his handlers. Or, it can be taken as the story of Marie, Jacques and Gerard and selected others who inhabit a rural French village, whose lives intertwine with the life of Balthazar. Indeed, this story could take place in a small Midwest farm town — you'll recognize people you know in the character types Bresson gives us.

As film critic James Hoberman observed, "This is the story of a donkey in somewhat the way that Moby Dick is about a whale." Delving deeper into Bresson's masterpiece, you will see the good and bad of mankind, and witness a story rich in spiritual allegory that can be interpreted many ways, in light of your own beliefs. And while most movies confuse action and noise with meaning, Balthazar is one of those rare movies that skips gratuitous extras and yet provides everything we need. Au Hasard Balthazar presents the simplest of stories with barely any embellishment at all, but by the time it's over there are countless meanings to draw from it.

Before you become immersed in, or overwhelmed by allegory, it is important to know this: Understanding Bresson's symbolism is not essential to understanding and appreciating this wonderful film. Analysis of Bresson and his films has spawned a huge body of work, the complexity of which tends to be the inverse of the simplicity that Bresson brings to the screen. What we take away from this film comes from our emotional connection with Balthazar the donkey. That connection, spurred by Bresson's uncanny ability to elicit our emotions, comes from what the individual viewer brings to the film, and builds upon our core (and sometimes hidden) feelings about love, empathy and foregiveness.

Instead of having actors fabricate emotions to put up on the screen, Bresson causes these emotions to well up spontaneously from within us. This is not an easy thing to accomplish, and sometimes just as hard to appreciate, but Bresson was one of the few directors who could do it consistently and make it look effortless. A perfect example is the final scene of the film, where, in its pathos, depth of association and emotional immediacy, Bresson leads us to experience one of the most evocative, sublime and affecting passages in the history of film.

It is remarkable how Bresson has fashioned a tragedy which evokes so much of our lost human ideals, and a love that endures all trials, in a story about an animal. The result is, despite appearances, not a film of gloom and depression, but of strange and ineffable beauty.

Just how does Bresson show such beauty and spirituality in a simple donkey?

This is one of the profound mysteries of Balthazar, which we'll pursue in the post-film discussion.

Balthazar will stay with you long after the lights go up. A film's effect is usually felt at the time we watch it, and its power lies in its immediacy. While Balthazar performs well in this fashion, one of Bresson's rare gifts was to create moments on film which have all the tentative and incomplete quality of actual experience, only to burn in the heart later with a mysterious sense of restored memory.

Balthazar remains as powerful today as when first released. In the blockbuster climate of 21st century cinema, Au Hasard Balthazar seems like a miracle, a breath of fresh air from another time and place, in which both artistic originality and the human spirit were equally valued. Compelling, humbling, and stunning in its visual construction, Au Hasard Balthazar is a one-of-a-kind film from an absolutely unique filmmaker.

Others have said it so well: A goodly portion of the foregoing has been condensed and concatenated from the writings of Daryl Chin and Doug Cummings, MastersofCinema.org; Chris Dashiell, CineScene.Com; Wheeler Dixon, All Movie Guide; Roger Greenspun, New York Times; Serdar Yegulalp, TheGline.Com and Jeff Shannon, the Seattle Times.

About The Film & Its Resurrection

ROBERT BRESSON'S Au Hasard Balthazar was released in 1966 and won the OCIC Gran Prix that year at the Venice Film Festival, the same year that the Battle of Algiers won the Golden Lion for Best Film at Venice. In 1967, the film won Best Film from the French Syndicate of Film Critics.

ROBERT BRESSON'S Au Hasard Balthazar was released in 1966 and won the OCIC Gran Prix that year at the Venice Film Festival, the same year that the Battle of Algiers won the Golden Lion for Best Film at Venice. In 1967, the film won Best Film from the French Syndicate of Film Critics.

AS WAS THE CASE with Army of Shadows (screened by CWC in 2007) and Battle of Algiers (screened by CWC in 2004) it took a few years for this film to reach America. In 1970, it was screened in the U.S. at film festivals and the NY Film Forum, celebrated by critics and festival attendees, did not receive a national roll-out and essentially disappeared from the American film scene.

BUT BACK IN 1970, American minds were elsewhere and the top movies were Patton, Tora! Tora! Tora!, A Clockwork Orange, M*A*S*H and Airport. Exhibitors and general audiences paid scant attention to the little-known director from France and his black-and-white parable about the meaning of life that featured a donkey, set in a rural French farm village.

THANKS TO RIALTO PICTURES, 33 years later there came a new 35mm print with new translations and new subtitles and the film was released in October, 2003. Amazingly, this was the first-ever theatrical release of this film in the U.S., which sadly did not include Cincinnati. Since then, the critics have again been effusive and the film has been excellently received by moviegoers at festivals, retrospectives, museum and film society screenings, etc.

The relentless commercialization of movies is understandable; people get rich off movies and more power to them. But there are other kinds of movies — those movies you carry inside you and that press on your chest — they exist nonetheless. French director Robert Bresson's 1966 film is being redistributed; there is no more important movie now in theaters. ~ L.A. Times

Au Hasard Balthazar makes large demands upon its audience, and in return confers exceptional rewards. It is the only absolutely essential moviegoing in New York. ~ New York Times

Why this film is important and why you should see it

There is really no other film like Au Hasard Balthazar; it is one of the few films that truly matter. This is a film you should see on the big screen in 35mm in a movie theatre, and one you'll want to watch again, perhaps at home, as it becomes richer with repeated viewings.

As film critic James Hoberman observed, "This is the story of a donkey in somewhat the way that Moby Dick is about a whale." Delving deeper into Bresson's masterpiece, you will see the good and bad of mankind, and witness a story rich in spiritual allegory that can be interpreted many ways, in light of your own beliefs. And while most movies confuse action and noise with meaning, Balthazar is one of those rare movies that skips gratuitous extras and yet provides everything we need. Au Hasard Balthazar presents the simplest of stories with barely any embellishment at all, but by the time it's over there are countless meanings to draw from it.

Before you become immersed in, or overwhelmed by allegory, it is important to know this: Understanding Bresson's symbolism is not essential to understanding and appreciating this wonderful film. Analysis of Bresson and his films has spawned a huge body of work, the complexity of which tends to be the inverse of the simplicity that Bresson brings to the screen. What we take away from this film comes from our emotional connection with Balthazar the donkey. That connection, spurred by Bresson's uncanny ability to elicit our emotions, comes from what the individual viewer brings to the film, and builds upon our core (and sometimes hidden) feelings about love, empathy and foregiveness.

Instead of having actors fabricate emotions to put up on the screen, Bresson causes these emotions to well up spontaneously from within us. This is not an easy thing to accomplish, and sometimes just as hard to appreciate, but Bresson was one of the few directors who could do it consistently and make it look effortless. A perfect example is the final scene of the film, where, in its pathos, depth of association and emotional immediacy, Bresson leads us to experience one of the most evocative, sublime and affecting passages in the history of film.

It is remarkable how Bresson has fashioned a tragedy which evokes so much of our lost human ideals, and a love that endures all trials, in a story about an animal. The result is, despite appearances, not a film of gloom and depression, but of strange and ineffable beauty.

This is one of the profound mysteries of Balthazar, which we'll pursue in the post-film discussion.

Balthazar will stay with you long after the lights go up. A film's effect is usually felt at the time we watch it, and its power lies in its immediacy. While Balthazar performs well in this fashion, one of Bresson's rare gifts was to create moments on film which have all the tentative and incomplete quality of actual experience, only to burn in the heart later with a mysterious sense of restored memory.

Balthazar remains as powerful today as when first released. In the blockbuster climate of 21st century cinema, Au Hasard Balthazar seems like a miracle, a breath of fresh air from another time and place, in which both artistic originality and the human spirit were equally valued. Compelling, humbling, and stunning in its visual construction, Au Hasard Balthazar is a one-of-a-kind film from an absolutely unique filmmaker.

Others have said it so well: A goodly portion of the foregoing has been condensed and concatenated from the writings of Daryl Chin and Doug Cummings, MastersofCinema.org; Chris Dashiell, CineScene.Com; Wheeler Dixon, All Movie Guide; Roger Greenspun, New York Times; Serdar Yegulalp, TheGline.Com and Jeff Shannon, the Seattle Times.

AS WAS THE CASE with Army of Shadows (screened by CWC in 2007) and Battle of Algiers (screened by CWC in 2004) it took a few years for this film to reach America. In 1970, it was screened in the U.S. at film festivals and the NY Film Forum, celebrated by critics and festival attendees, did not receive a national roll-out and essentially disappeared from the American film scene.

BUT BACK IN 1970, American minds were elsewhere and the top movies were Patton, Tora! Tora! Tora!, A Clockwork Orange, M*A*S*H and Airport. Exhibitors and general audiences paid scant attention to the little-known director from France and his black-and-white parable about the meaning of life that featured a donkey, set in a rural French farm village.

THANKS TO RIALTO PICTURES, 33 years later there came a new 35mm print with new translations and new subtitles and the film was released in October, 2003. Amazingly, this was the first-ever theatrical release of this film in the U.S., which sadly did not include Cincinnati. Since then, the critics have again been effusive and the film has been excellently received by moviegoers at festivals, retrospectives, museum and film society screenings, etc.